by Matias Travieso-Diaz

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium

William Butler Yeats, Sailing to Byzantium

In early 1201, Prince Alexios Angelos of Byzantium and I, his valet, were rescued through bribery after six years of confinement in Constantinopolis’ Prison of Anemas. Pisan merchants, whom we met them outside the prison, spirited us away in their galley.

We landed in Pisa and were transported overland to the Hohenstaufen Castle in Göppingen, home of Duke Philip of Swabia. Prince Alexios’ sister Irene was married to the Duke and received us with open arms; not so much her husband, who was fighting for the throne of Germany and had greater concerns than caring for fugitives from far-away Byzantium.

It is always frigid and windy in Hohenstaufen, which sits on a hill that overlooks the Rems and Fils rivers. We froze in the keep, alone, and tasted the bitter bread of exile. We longed to return to beautiful Constantinopolis, the queen of cities, where it is always warm and sunny. There was scant news of Alexios’ father, Isaakios II Angelos, who had been deposed, blinded, and imprisoned. Presumably, he was still alive; his deposer, Alexios III Angelos, was not ready yet to stain his hands with the blood of his own brother.

The Duke was celebrating Christmas and had assembled his court for a lavish feasting season. Among the guests was his cousin Boniface, Marquess of Montferrat. Boniface had just been chosen to lead a Fourth Crusade that was being organized, and had come to seek Philip’s support.

My Prince met Boniface at one of the Christmas banquets. Boniface regaled Alexios with tales of his military exploits and bragged that he could help Alexios’ father regain the throne of Byzantium. Alexios was taken with the idea.

Duke Philip was drawn into the conversation, and suggested that Boniface use his position as leader of the upcoming Crusade to restore Alexios’ father to power. This was a tricky idea, though, for the Crusades’ goal was to wrestle the Holy Land from the Muslims, not fight other Christian nations.

The night of that banquet, while readying Prince Alexios for bed, I heard from his inebriated lips an account of his conversations with Boniface and Philip. I cowered in fear. I was only a young child when slavers abducted me from my village and sold me to a Byzantine official. My master had brought me to Constantinopolis to become his confidential secretary when he went to serve at the palace. I thus kept current on Byzantium’s world affairs, and knew that the Frankish longed to conquer the Eastern empire.

Because of our years of imprisonment together I was freer to share my views with my master than a slave should be. “The Frankish covet the riches of our empire. We cannot trust them and should not make deals with them!” I urged.

Alexios struck me on the mouth. It was a feeble blow, for he was not a strong man and was weakened by wine. “How dare you, slave, second-guess your master? I should have you flayed!!”

I was not badly hurt, except in my pride. I lowered my head and responded meekly: “Despotes, my life is yours to dispose of as you wish. But I would be untrue if I did not warn you of the grave danger in the alliance that is being proposed to you. I watched that man Boniface during the banquet. He is a ruthless man, who shall seek to bend you to his will. You must not allow him and his Crusaders to come anywhere near Byzantium!”

Alexios raised his arm, intent on striking me again, but the effort was too much in his condition. He merely replied with scorn: “Though you may think otherwise, I chose you to be my servant, not my counsellor. So, shut up and help me disrobe!”

Without more, he flung himself on his bed, still fully dressed. In the next minute he was snoring loudly.

#

Prince Alexios visited Rome early next year and promised the Pope that he would pledge a large sum to the Crusaders’ cause if they would assist him and his father in regaining power. With those moneys, the Crusade could finally get underway. The Pope agreed not to oppose the Crusaders’ potential diversion into Byzantium, but specifically told them not to attack any Christians, including the Byzantines.

#

Another figure then entered the stage: Enrico Dandolo, the Doge of Venice. The merchant republic and Byzantium were bitter commercial rivals and had fought many wars, directly and through proxies, in their attempts to monopolize trade in the Mediterraneum. Dandolo himself was no friend of Byzantium and was rumored to have lost his eyesight while fighting us. Thus, his involvement in the upcoming Crusade was most troubling.

Dandolo agreed that Venice would provide transportation and most provisions for the Crusader army but demanded that the Crusaders first make a show of force at Zara, a Christian city on the Dalmatian coast that once had been controlled by Venice and was now a Hungarian possession. From Zara the crusader army would set sail for Byzantium.

The Crusade fleet arrived in Zara in November. The sheer size of their fleet intimidated the Zarans, but they held fast against the intruders. The Crusaders attacked the city, and after five days of fighting took it on November 24, 1202. Upon capture, the city was thoroughly sacked.

In late December Prince Alexios and I arrived in Zara. Its conquest was the final alarm bell that I needed before frantically pleading with Alexios to put an end to the venture. He rejected my pleas and informed me that he had promised to pay two hundred thousand silver marks to the Crusaders and their Venetian allies if he and his father were restored to power. As before, my objections were brushed aside by the Prince.

#

It was New Year’s Day, 1203 and the Crusader fleet was getting ready to leave Zara for Constantinopolis. Prince Alexios and I attended early morning New Year services at one of the few churches that had not been destroyed by the Crusaders. As we were returning to our quarters, I pointed to the charred ruins of a palace and remonstrated with the Prince:

“How can you persist in seeking the help of these barbarians, seeing what they are capable of doing? Zara was a Popish city, and it was not spared. What will they do to Constantinopolis, a far greater place? What will become of our palaces, our Hagia Sophia, the vast riches that we have gathered over the last nine centuries? Do you not see that you are putting all of Byzantium at grave risk?”

Alexios cut me short. “It is my divine right to become Basileus Autokrator. I can deal with the Frankish and the Venetians, and to disagree with me is traitorous. I will have no more of your talk, slave!”

“My Prince, you are wrong, and you are gambling with the lives of our citizens. I have had visions of our proud city being laid low by the Frankish scum. Please reconsider….”

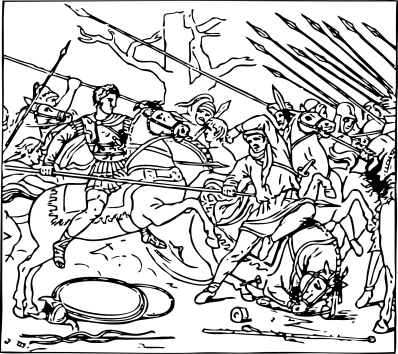

Alexios did not let me finish. In a rage, he jumped at me and started to pummel me violently. I took no measures to protect myself but, as he was drawing blood from my face and crushing my cheekbones, I grasped his arms to restrain him. This drew him even more incensed; somehow he freed himself and pulled a dagger from his cloak, bellowing: “You villain, you dare lay hands on your Prince! For this you shall die!!”

I tried to run away, but lost footing and fell to the ground. Alexios stood above me and raised the dagger to slay me. To protect myself, I grabbed his wrist and attempted to dislodge the weapon. Alexios lunged at my prone figure, stabbed me on the arm, lurched forward to strike another blow, lost balance and fell on top of me. We struggled until I overcame him.

I got up and tried to help the Prince to his feet. Alexios’ dagger was protruding from his chest and he was not moving. A pool of blood was already forming beneath his body. There was blood on my face, my garments, my slashed arm.

I ran away, crying for help, but due to the holiday Zara’s ruins seemed empty and nobody answered my calls. After a while, I returned to the Prince, who lay where he had fallen. He was dead, and his body was already starting to cool. I covered him with my soiled cloak and left for the Crusaders’ camp, dripping blood from my many wounds.

#

I was seized by an overwhelming feeling of guilt. I had slain my master. I had committed a horrendous crime for which no pardon was possible. I thought of killing myself but I had no weapons: Alexios’ dagger was still buried in his chest.

I began shuffling like a condemned man, step by painful step, in the direction of the port, where I expected I would be put to death by the Crusaders the moment I confessed my crime. But as I walked, I considered my situation with a cooler head. I could testify if necessary that my killing of the Prince had been an accident, for which I should not be held responsible. Moreover, offering myself for execution would not bring the Prince back to life. Alexios’ death had been decreed by divine providence, as a way to prevent the greater ills that would have occurred had the expedition against Constantinopolis been carried out.

I then decided that a fitting punishment for the Prince’s death would be for me to stay alive and devote my life to prayer and good deeds in the memory of the man I had slain. I turned inland and proceeded towards the hills to the east. I expected to be seized at any moment, and was sure that the Crusaders would send search parties in all directions and would capture me in no time.

But nobody came after me. Perhaps their finding the trail of my blood had left the impression that I, too, had perished.

In the afternoon, I arrived at a village and found people who spoke Greek and directed me to an Orthodox monastery a three hour walk away. I took refuge there and never left.

Some may question the veracity of my account and accuse me of deliberate murder, given my opposition to the fatal course of action on which the Prince was about of embark. I shall also leave for others to judge whether my flight from the Crusaders’ camp was driven by wisdom or cowardice. Nobody is left to judge me and the truth does not matter anymore.

#

It has been twenty years since my crime, and the world has changed a lot since then. With the death of Prince Alexios, the Crusade came to a halt, but Pope Innocentius III continued to preach for its resumption and in 1205 the Fourth Crusade belatedly left for Egypt, forsaking Constantinopolis. The Crusaders captured Alexandria on the Nile delta after a fierce battle. From there, they drove along the coast like a sandstorm, defeating the Ayyubid successors of Saladin and conquering back Jerusalem in 1206. The Kingdom of Jerusalem was re-established and Boniface became its first ruler. More Crusaders and Christian settlers arrived in subsequent years, establishing a new kingdom that abuts the southern border of Byzantium, such that they can mutually defend each other.

Isaakios died in prison, and not much later his treasonous brother was deposed and executed. Byzantium now has a new ruler who has led the empire to many a victory over its foes. Constantinopolis has been able to repel any invaders and Byzantium endures, and with God’s favor will remain the greatest empire on Earth for a thousand more years.

I will go to my grave soon. I still grieve the death of my master, but do not lament my acts or their beneficial results.

~

Bio:

Matias Travieso-Diaz was born in Cuba and migrated to the United States as a young man. He became an engineer and lawyer and practiced for nearly fifty years, whereupon he retired and turned his attention to creative writing. Over sixty of his stories have been published or accepted for publication in paying short story anthologies, magazines, blogs, audio books and podcasts; some of his other stories have received “honorable mentions.”

Philosophy Note:

The year I was born Harold Lamb’s The Crusades was published. I read it first as a teenager and was captivated by the deeds of Christian and Muslim leaders whose fighting over the Holy Land informed the future of the Middle East for many centuries to come.

I was particularly drawn by the disastrous fiasco that became the Fourth Crusade, an affair that ended up overthrowing a thousand year empire that served as a buffer between East and West. In addition to destroying one of the great sources of the world’s cultural heritage, it led to a fractious distribution of power that continues to affect the thinking and behavior of millions of people today.

Harold Lamb’s account of the Fourth Crusade is eminently readable and I recommend it to anyone who wishes to reflect on one pivotal moment in history and wonder “what if” a callow youth who gave away a great empire had failed to do so.